We recently had the chance to connect with Dr. Lance Bennett and have shared our conversation below.

Lance, a huge thanks to you for investing the time to share your wisdom with those who are seeking it. We think it’s so important for us to share stories with our neighbors, friends and community because knowledge multiples when we share with each other. Let’s jump in: What are you being called to do now, that you may have been afraid of before?

I am being called to lead publicly and unapologetically—to claim the Institute not simply as a set of programs, but as a moral and intellectual project rooted in the common good. Earlier in my journey, I was hesitant to step fully into that role. I worried about legitimacy, about whether the work was “big enough,” funded enough, or sanctioned enough by traditional institutions to be taken seriously. That fear often showed up as over-preparation, waiting for permission, or trying to fit the Institute into familiar organizational boxes.

What has shifted is a deeper trust in the work itself and in the communities it serves. I now understand that the Institute exists precisely because many existing structures are unable—or unwilling—to hold the kinds of questions, relationships, and learning we need right now. I am being called to name that clearly, even when it disrupts expectations about higher education, leadership, and expertise.

This calling also requires me to center fellowship as a serious mode of teaching and learning, not an accessory to it. It means building spaces where people gather across difference, not to be managed or optimized, but to think, learn, and imagine together. I once feared that this emphasis on relationship and formation would be dismissed as soft or impractical. I now see it as essential infrastructure for social progress.

Ultimately, I am being called to stop shrinking the vision for the sake of comfort and to steward it with courage—inviting others into something that is still becoming, but deeply necessary.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

My name is Dr. Lance Bennett, and I am the founder and president of The People’s Institute for the Common Good, a learning and civic formation organization based in Dallas, Texas. My work sits at the intersection of education, community, and imagination—asking how we might learn with one another in ways that strengthen our shared sense of responsibility for the world we inhabit together.

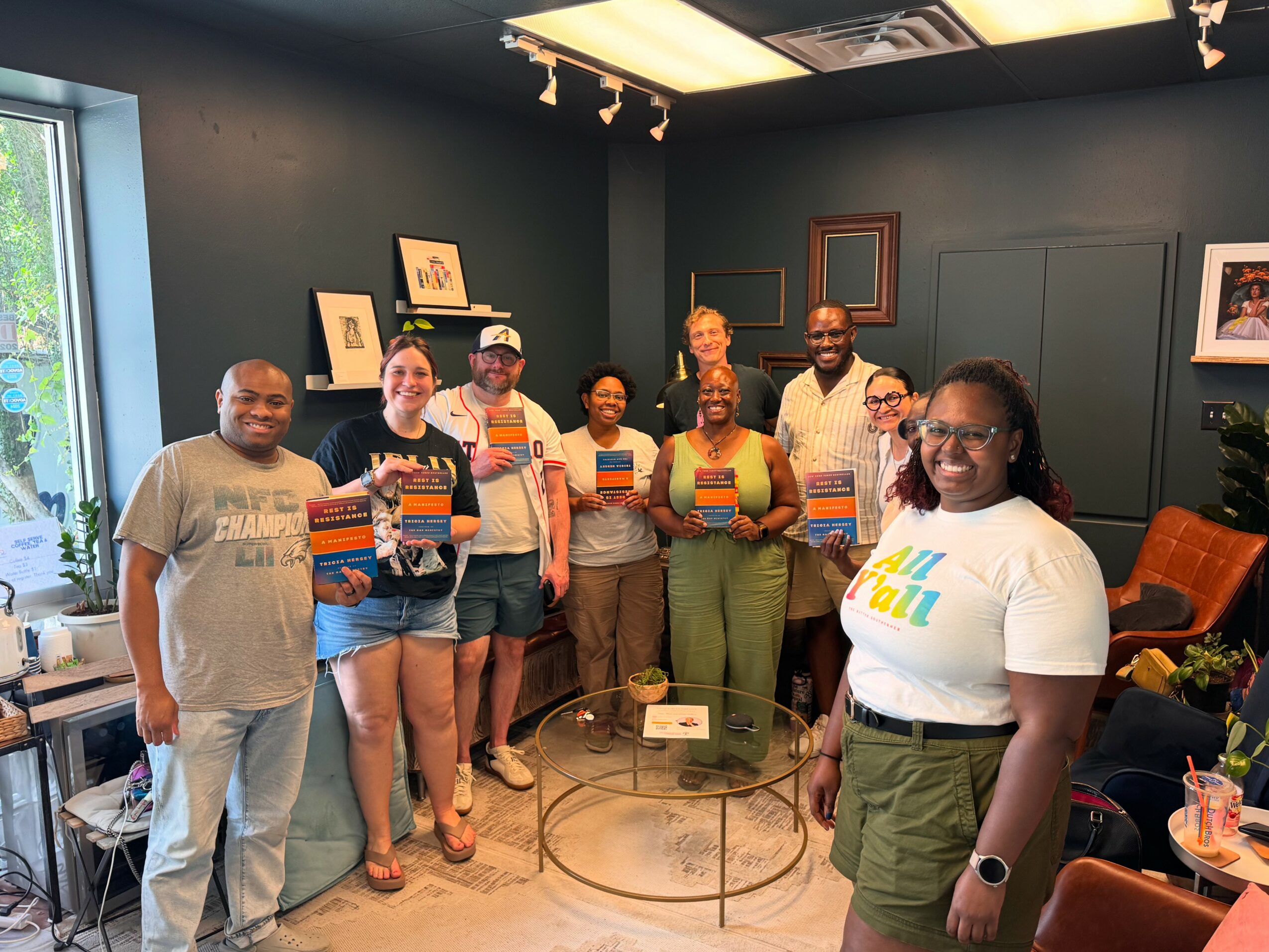

The Institute exists because I believe learning is not confined to classrooms or credentials. Much of what shapes us—our values, our commitments, our sense of purpose—happens in community, through conversation, fellowship, and shared inquiry. We design programs that bring people together across difference to think deeply about social progress, culture, and the common good, including book clubs, public conversations, and our forthcoming Distinguished Speaker Series.

What makes the Institute unique is our emphasis on fellowship as a serious form of teaching and learning. Rather than prioritizing speed, scale, or productivity, we prioritize formation—creating spaces where people can slow down, listen well, and imagine futures that are more just and humane. My background in higher education and organizational culture shapes this work, but at its heart, the Institute is about people: their stories, their questions, and their capacity to learn together in good company.

Great, so let’s dive into your journey a bit more. What’s a moment that really shaped how you see the world?

A formative moment in how I came to see the world was my undergraduate education at Eastern University. Eastern’s motto—faith, reason, and justice—was not just a slogan; it was a lived framework that shaped how learning connected to responsibility. I was introduced to the idea that education is not only about personal advancement, but about moral obligation—about asking what kind of good our knowledge makes possible in the world.

At Eastern, faith and reason were held in conversation rather than in competition. I learned that rigorous thinking could coexist with deep conviction, and that justice required both intellectual honesty and relational commitment. That integration reshaped how I understand success, leadership, and purpose.

Most importantly, Eastern helped me see that doing good in the world is not abstract or aspirational—it is practiced through everyday choices, relationships, and institutions. That insight continues to guide my work today. Whether through teaching, convening, or building learning communities, I carry forward that formative lesson: that education at its best forms people not just to know more, but to care more, and to act with intention toward the common good.

Was there ever a time you almost gave up?

Yes—there was a time when I came very close to giving up, and it happened during my first doctoral program. Earning a doctorate had been a lifelong dream of mine, something I imagined for myself from a very young age. But once I was in the PhD program, it became clear that the environment was not supportive. I consistently ran into obstacles, lacked meaningful faculty mentorship, and found myself navigating a culture that felt more toxic than formative.

For a long time, I internalized that struggle as a personal failure. I questioned whether I belonged in doctoral study at all and whether the dream I had carried for so many years was actually meant for me. That period was deeply discouraging and took a real toll on my mental health.

Ultimately, I made the difficult but necessary decision to step away. Choosing my well-being over a credential felt like a loss at the time, but it turned out to be one of the most important decisions I’ve ever made. Within a year, I enrolled in an EdD program that aligned far better with my values, learning style, and goals. I thrived in that environment and successfully completed the degree.

That experience reshaped how I think about success: sometimes perseverance means pushing through, but sometimes it means having the courage to walk away and choose a healthier path forward.

Alright, so if you are open to it, let’s explore some philosophical questions that touch on your values and worldview. Whom do you admire for their character, not their power?

I deeply admire bell hooks for her character rather than her power. What has always stood out to me about her work is the way she led with integrity, care, and intellectual honesty. She wrote with clarity and courage, but also with deep compassion—refusing to separate love from justice or theory from lived experience.

bell hooks never positioned herself above her readers. Instead, she invited people into rigorous reflection, asking us to examine ourselves, our relationships, and the systems we inhabit. Her commitment to naming oppression was matched by an equally strong commitment to healing and transformation. That balance—truth-telling paired with love—requires a kind of moral courage that has nothing to do with authority or status.

What I admire most is how accessible she made serious ideas. She believed that education should liberate, not intimidate, and that learning belonged to everyone. That posture continues to shape how I think about teaching, community, and the common good. bell hooks reminds me that character shows up not in how loudly we speak, but in how faithfully we hold space for others to learn, grow, and become.

Okay, so let’s keep going with one more question that means a lot to us: What is the story you hope people tell about you when you’re gone?

I hope people say that I helped create spaces where they felt seen, challenged, and invited to grow. I want the story to be less about titles or accomplishments and more about how people experienced learning and community in my presence.

I hope they say I believed deeply in the power of fellowship—that I took relationships seriously as a form of learning and knowledge, and that I worked to build an nstitution that honored people’s dignity rather than reducing them to outcomes or metrics. If people say that I listened well, asked meaningful questions, and made room for others to bring their full selves into the work, I would consider that a life well lived.

I also hope the story includes courage: that I chose the harder, more humane path even when it was less certain or less rewarded. That I resisted the urge to replicate systems that exclude or exhaust, and instead tried to imagine alternatives rooted in education and the common good.

Ultimately, I hope people say that being in community with me helped them remember who they were called to be—and that the work continues, carried forward by others, in good company.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://instituteforcommongood.substack.com/

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/instituteforcommongood/?hl=en

- Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/company/the-people-s-institute-for-the-common-good/?viewAsMember=true