Today we’d like to introduce you to Ali Davis.

Hi Ali, it’s an honor to have you on the platform. Thanks for taking the time to share your story with us – to start, maybe you can share some of your backstories with our readers.

From the ages of approximately 6 months to 19 years of age, I was a victim of torture at the hands of one of my parents (more common than you may think!!). Now I’m funding humanitarian aid for survivors of non-war-related childhood torture through art inspired by graffiti.

Graffiti has been called “the language of the ignored,” and this statement has resonated with me since long before I created the piece that would eventually put Pretti Graffiti on the map and serve as the foundation for the first nonprofit dedicated to rendering humanitarian aid to survivors of non-war-related childhood torture in the US.

Before we explore the intricacies of the definition of “non-war-related childhood torture” (and we will explore them because how can we begin to address a problem that doesn’t even have a definition), let me take you back to the night that I created that very first piece.

The night that the first Pretti Graffiti piece was brought into existence, my focus was not on humanitarian aid.

My focus was on survival.

My art has never been out of a desire to create, rather a desperation to survive.

A few hours prior, I had sat down to watch Hannah Gadsby’s first Netflix special Nanette – as I often do when the world begins to feel too much.

This was approximately my ninth time of watching Nanette, and as I clicked off my TV, I felt something urgent bubbling up inside my soul.

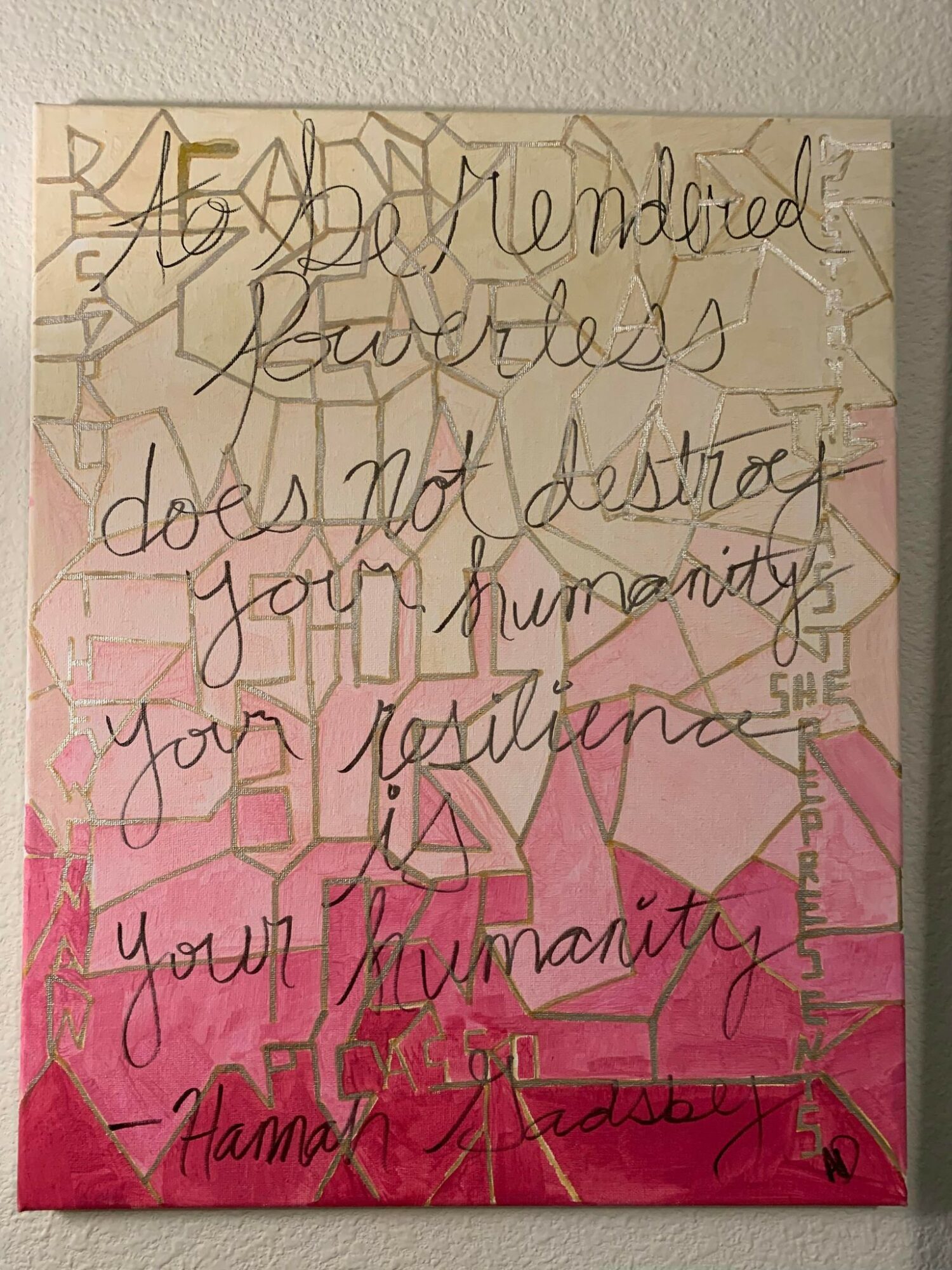

So, I grabbed a canvas and began scrawling the words of Picasso, which had been introduced to me by Hannah the first time I watched their Netflix special, and these words were: “Each time I leave a woman, I should burn her. Destroy the woman, destroy the past she represents.”

As I defaced the canvas with my marker, it wasn’t words I found pouring out of me; it was rage and anguish.

I thought of all the times my story had been taken from me.

And how I would no longer allow those responsible for the harm done to me to destroy me, my story, or hide from the past my existence represents.

After pouring this quote out onto the canvas, I spent the next 2 hours making these words unrecognizable by drawing connecting lines between every available point of every letter.

Watching these words – and more importantly, what they represented – disappear by the actions of my hands healed more inside my soul than 100 years of therapy ever could.

[Therapy is extraordinarily important. I am using hyperbole to attempt to explain the indescribable experience this first piece brought to my healing journey.]

By the time I finished this process, several hours had passed, and I knew exactly how I wanted the canvas to look when it was finished.

I filled in the spaces between where these words lay hidden beneath the surface with various shades of pink; in doing so I like to think I honored the work that survivors do every day to create beauty and meaning out of the pieces our lives are shattered into by these systems of oppression.

Finally, across the nearly finished canvas, I wrote one of my favorite quotes from Nanette: “To be rendered powerless does not destroy your humanity. Your resilience is your humanity.”

This simple action felt like a powerful reclamation of toxic, oppressive narratives and the beginnings of replacing them with inspiring and inclusive alternatives from people unjustly forced into the margins for far too long.

Very of the moment. Very symbolic.

I had no idea at the time what I had stumbled upon – remember, I was simply trying to make it to the next sunrise.

In the months that followed, I simply could not stop making art.

I covered quotes from Supreme Court justices, quotes from holy books, and quotes from predatory celebrities with inspiring words from queer poets, trauma survivors, and neurodivergent authors, and before I knew it, I had walls full of art and a heart full of hope* for the first time in a very, very long time.

I learned Nietzsche’s lesson long before I ever knew he existed.

[“Hope, in reality, is the worst of all evils because it prolongs the torments of man.” – Nietzsche]

As people began to resonate with the story behind my art and my pieces found homes from coast to coast, I started to gather the courage to begin sharing my story.

I began by simply sharing facts about childhood torture and how it differs from child abuse*, and other survivors flooded into my comments on TikTok sharing their own stories and reveling in the fact that we were collectively carving out a space for our stories to have representation in media.

[*I am sure that you’re wondering what the difference is. To summarize without painting too graphic a picture: abuse and torture can have an overlap in specific acts; however, in torture, the perpetrator exploits the victim’s access to the necessities of life (breathing, food, water, hygiene, etc.) in order to establish complete domination over their victim and “break” them – physically and/or mentally. There’s a lot more to it than this, and you can read more about that part of my story on Medium, but this information suffices for purposes of what you came here to read today.]

When I learned a few months later that the cost of treating the health conditions that result from Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) eclipses 950 BILLION dollars in North America alone annually and that zero organizations dedicated to humanitarian aid for survivors of non-war-related childhood torture exist in the US, the mission of Pretti Graffiti Foundation was realized.

Would you say it’s been a smooth road, and if not, what are some of the biggest challenges you’ve faced along the way?

Not to put too fine a point on it but, no. It has not been a smooth road. There is no road to speak of.

A road already exists.

My posts were among the first on the topic, if not the first.

When I started speaking out about this, #childhoodtorturesurvivor wasn’t even recognized on TikTok.

Now, it has 2.5 million views and thousands of participants.

As you know, we’re big fans of you and your work. For our readers who might not be as familiar, what can you tell them about what you do?

I am the founder and executive director of the Pretti Graffiti Foundation – a nonprofit established to fund humanitarian aid for survivors of childhood torture through art sales, as well as through grants and individual donors. My proudest accomplishment is that I frequently remind myself of one of my favorite quotes: “I love when people who have been through hell walk out of the flames carrying buckets of water for those still consumed by the fire.” (Stephanie Sparkles)

The thing that sets me apart from others is…quite literally…everything.

To my knowledge, there are no other organizations working to offer humanitarian aid to survivors of non-war-related childhood torture in the US.

The UN provides funding for survivors of state-sanctioned torture, and HHS offers assistance to individuals who were tortured in other countries and are now living in the US, but both of these eligibility requirements exclude survivors like me – a group growing by approximately 36,000-72,000 cases per year*.

[A very rough estimation based on nationwide child abuse statistics + child torture statistics from Knox et al. estimation of 1-2% of children medically evaluated for abuse meeting criteria for torture. This number is highly likely to be inaccurate, which highlights the significant need for more research on this topic – something I plan to help fund through the Pretti Graffiti Foundation.]

What do you like and dislike about the city?

I love the architecture – but not in the way most people would assume I would as someone who is living in the metroplex that boasts the “best international skyline” as of 2014. What I love about our architecture is the unassuming places where people have carved out lives for themselves.

The graffiti under the bridges.

The prying of nails that drove 4 inches of rusty inconvenience between life and death in the elements.

The evidence that otherwise forgotten lives leave behind – forcing acknowledgment of an existence that passes by, ignored in plain sight.

Being the person of multiplicity that I am, it should come as no surprise that my favorite thing about our city is also a representation of the thing, I love the least about our city – income inequality and a growing wealth gap.

Like many other survivors, I admire resilience, yet am simultaneously exhausted by the unnecessary conditions that require it of myself and others.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.prettigraffiti.org

- Youtube: https://www.tiktok.com/@eleven17creations

- Other: https://prettigraffiti.medium.com/i-survived-bill-gothards-cult-now-i-m-on-a-mission-to-secure-humanitarian-aid-for-other-ce35c54b37f5