Today we’d like to introduce you to Brenda Zlamany.

Hi Brenda, so excited to have you with us today. What can you tell us about your story?

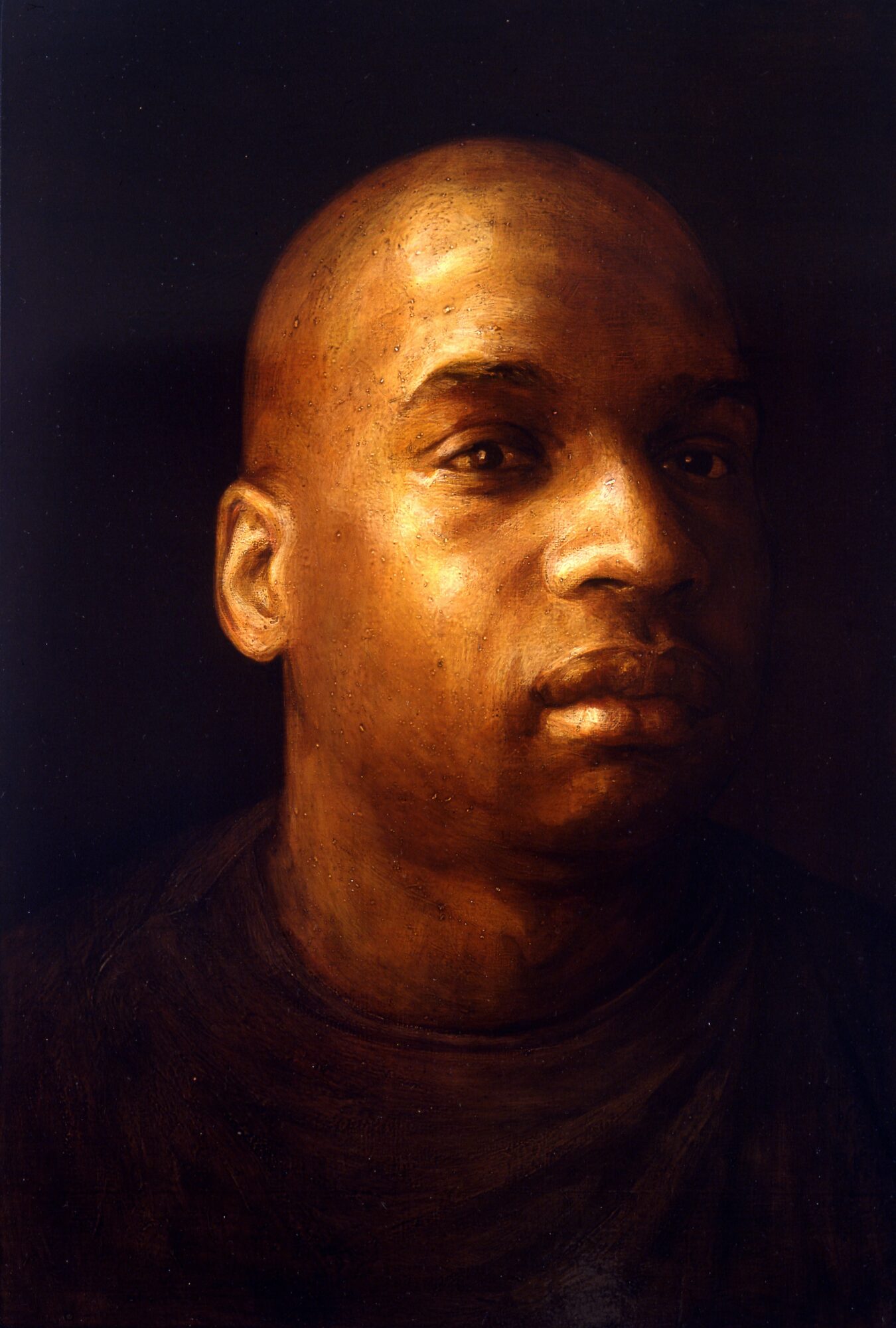

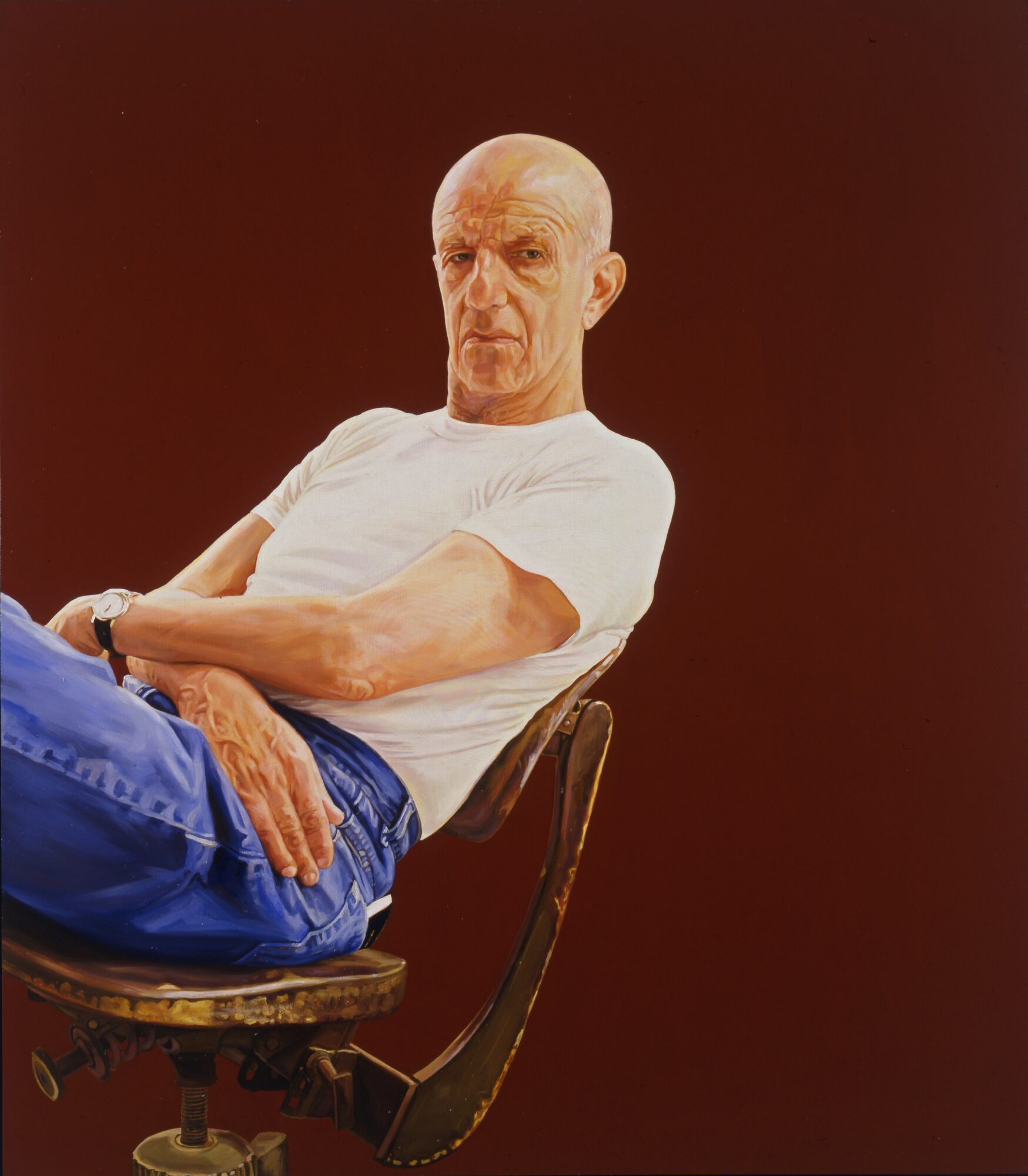

When I was an art student in the late 70s, figurative painting and the production of beauty were considered white-male relics, off-limits to serious female artists. After graduation, I began studying the works of the “masters” in museums and painting small, jewel-like still life’s of dead animals, in part because they could hold poses longer than people but also because their textures and colors were ideal for the glazing and oil painting techniques that I was interested in learning. Influenced by feminism and minimalism, I painted my first portraits, of twelve bald male artists, in an attempt to reverse the traditional male gaze on the female subject.

Reinvigorating portraiture has been the focus of my work since that first portrait exhibition. The show’s success led to important commissions, which in turn expanded the scope of my practice to include historical figures. For instance, The New York Times Magazine invited me to paint Jeffrey Dahmer for an artist-created issue on evil, Marian Anderson for an article by Jessye Norman, and Osama bin Laden for the cover of the September 11, 2005, issue. My latest public works, ambitious large-scale group portraits of under-represented women and people of color, are helping expand diversity in the iconography of public spaces.

From the start, portraits of other artists have been at the center of my practice. Because I work with my subjects directly and have also posed for many of them–including David Hockney, Alex Katz, Renee Cox, and Lyle Ashton Harris–my painting project is part of the contemporary conversation on portraiture. Many of us have depicted the same subjects, ourselves or each other, and our portraits form a community of images of artists by artists. “Painters Painting Painters: A Study of Muses, Friends, and Companions,” on view until September 25th at the Green Family Art Foundation in Dallas explores this theme, and features my painting “Self Portrait Painting David Hockney Painting Oona” along with David Hockney’s portrait of me, “Brenda with Cigarette,” and works by over 20 other artists.

With the birth of my daughter in 2000, I began looking closer to home for inspiration. The resulting portraits formed my 2007 exhibition, “Facing Family,” and led to a regular practice of portraits depicting my family. That same year, I traveled to remote areas of Tibet with my seven-year-old daughter (a fluent Mandarin speaker). I did not intend to create a portrait project–a previous trip to Southeast Asia in 1997 had led to a landscape show–but my interactions with Tibetans were wonderful, and traveling with a Mandarin-speaking child delighted people and opened doors. This experience led to an interest in painting people outside of my immediate circles.

In 2011, I created an ongoing, multi-year project called “The Itinerant Portraitist.” In this project, I travel the globe to explore the positive effects of painted portraiture. After each excursion, I create a multimedia installation to share my discoveries with the public. Stories are at the heart of “The Itinerant Portraitist,” and I film conversations while simultaneously painting portraits. Each painting represents a relationship, and these watercolors–unlike my oil paintings, which I make over months from a combination of sketches, photos, and sittings–are always done from direct observation in a single sitting with the subject present. “The Itinerant Portraitist” allows me to explore critical social issues and has given me opportunities to collaborate with communities, filmmakers, and musicians.

My latest work, which began during the COVID lockdown, is inspired by the circus. The circus paintings, which draw on the technical complexity of my commissioned works, serve as a metaphor for these challenging times.

We all face challenges, but looking back would you describe it as a relatively smooth road?

I grew up as a left-handed, dyslexic child in the 60s–a period when dyslexia were not discussed, let alone treated. I attended a traditional Catholic school, where my left-handedness was seen as sinister and right-handedness was enforced through endless punishments, including sitting on the offending hand to keep from using it. As a result, I did not read and write fluently until third grade. I compensated for my inability to read by focusing on my artwork, redeeming myself with the nuns on holidays when I was called upon to decorate the church. When I was six, the nuns asked the kids in my class what we wanted to do with our lives. My first career choice was to be an astronaut, but they said that was only for boys, and my second choice, a nun, was not for lefties. Being an artist was my third career choice, and in the end, it was the best choice for me.

I also grew up in a family where achievement was not valued, especially for girls. Funds were set aside for my wedding but not for college. I looked outside of the family for role models and at thirteen, I started hitchhiking after school as a way of meeting people. I’d pick a general direction at random and interview the drivers who picked me up about their life choices until I turned around and hitchhiked home for dinner.

Through hitchhiking, I became good at interpreting faces. When a car pulled over, I’d poke my head into the window and study the driver’s expression. I only had a few seconds to read every line. If I got it wrong, there were consequences. Through these impromptu glances, I became an expert, and the skills I developed then continue to play a role in my ability to quickly capture complex psychological moments in my portraits.

When I was fourteen, a chance encounter changed the course of my life. While hitchhiking, I was picked up by a New Haven high school teacher whose husband was the head of the Yale Art Gallery. They invited me for dinner at their home in New Haven, where they had installed an amazing art collection. Inspired, I showed them some of my drawings. One thing led to another, and I was admitted to a selective high school focused on the arts and a pre-college program at Yale. This eventually led to a full scholarship at Wesleyan University, and the friendships that I formed there with other artists continue to be central in my life and my career.

Appreciate you sharing that. What else should we know about what you do?

I have painted over two thousand watercolor portraits in locations all over the world with “The Itinerant Portraitist,” an issue-driven project that changes with every chapter. “888: Portraits in Taiwan,” funded by a Fulbright fellowship in 2011, was the inaugural chapter. Since then, I have portrayed girls in an orphanage in the United Arab Emirates, concertgoers in Oxfordshire, artists in Brooklyn, taxicab drivers in Cuba, nursing home residents in the Bronx, people affected by climate change in Florida, California, and Alaska, visitors to a camel festival in Saudi Arabia, socially distanced mask wearers in New York, and Ukrainian refugees in Bratislava.

In 2017, I collaborated on my first film with the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Aaron Kernis about my nursing home project. The film, “100/100,” was an official selection in several festivals, including the Berkshire International Film Festival and the Greenpoint Film Festival, where it won Best Documentary Short.

Since 1982 my work has appeared in over a dozen solo exhibitions and numerous group shows in the United States, Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Museums that have exhibited my work include the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei; the National Portrait Gallery of the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Denver; Frankfurter Kunstverein, Germany; the National Museum, Gdansk, Poland; and Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent, Belgium.

My work has been reviewed in Artforum, Art in America, ARTnews, Flash Art, the New Yorker, the New York Times, and elsewhere and is held in the collections of the Cincinnati Art Museum; Deutsche Bank; the Neuberger Museum of Art; the Virginia Museum of Fine Art; the World Bank; Yale University; and Rockefeller University.

In 2015, I won the competition to paint Yale’s first seven women PhDs, which led to important public works such as Five Trailblazing Women Scientists at The Rockefeller University (2021) and a portrait of feminist icon Elga Wasserman scheduled for unveiling at Yale University in 2022.

What matters most to you? Why?

Iconography is powerful. It affects how people see themselves and one another, consciously and unconsciously. Encouraging people to examine and control how they are depicted can lead to empathy and open channels of communication. To explore this idea through portraiture, I created “The Itinerant Portraitist.” My large-scale portrait commissions also engage with these important issues through the crucial work of getting overlooked historical figures–women and people of color–on the walls of public institutions.

I am interested in the multifaceted nature of portraiture in the digital age. Far from becoming obsolete, the painted portrait has been renewed in the postmodern, post-photography age. In portrait painting, a connection between the artist and the subject is created by the act of building an image stroke by stroke. This connection is unusual in a time of virtual reality and high-speed, mediated experience. There remains, however, much to be explored in the question of who is portrayed and how. I hope to expand the boundaries of portraiture by creating works with and about people who are underrepresented in society and in art.

Contact Info:

- Website: https://www.brendazlamany.com

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/brenda_zlamany/?hl=en

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/brenda.zlamany

Image Credits

Zlamany_Dallas_

Robert Lowell Zlamany_Dallas_

Jenny Gorman Zlamany_Dallas_

Ian Christman Zlamany_Dallas_

Ian Christman