We’re looking forward to introducing you to Thomas Riccio. Check out our conversation below.

Thomas , so good to connect and we’re excited to share your story and insights with our audience. There’s a ton to learn from your story, but let’s start with a warm up before we get into the heart of the interview. What is a normal day like for you right now?

I wake when my body decides. Coffee espresso outside. Look at the vines on salvaged metal trellises from a scrapyard. In fall, they’re changing in ways I can feel but not name. A bird I don’t recognize. Clouds are performing their dissolution. I’m not observing—I’m participating. The world tells me what it’s doing if I stand still enough. I pet my dogs, Oskar and Pierre. I love them so.

Then I work on my book. Every sentence is a translation from a language of textures and colors that don’t exist in normal light. I write, delete, write again. The wrongness teaches me something. Afternoons, I bike and daydream. I let my mind wander sideways through connections. How AI transformer architecture mirrors mushroom networks of plant intelligence, how indigenous knowledge systems operated without centralized structures, and how my thoughts right now are assembled from fragments that aren’t mine. Keep the body busy, mind loose—that’s when ideas arrive.

Tonight: wine someone gave me, fish that used to swim, and vegetables that remember the earth. I’m eating the past tense of living things. Sometimes I call colleagues, friends, and relatives in other time zones. We’re all floating in the same digital space, which might be more real than physical space now. Before sleep, I write, read, watch a screen, or wander. I think or write without insights—just present and letting time happen.

Sometimes I wake at 3 AM and write down dreams as they evaporate. Here’s the thing about retired life: I’m working on paying attention. On staying permeable to coincidence, which is how the world thinks out loud. On being generous with what I know because hoarding is spiritual constipation. Sometimes everything clicks—the dream, the book I just read, the food just eaten, the way Oskar looked at me—and I see what wants to emerge next.

You can’t force life. You create conditions: attention, openness, daydreaming. Showing up even when nothing seems to be happening. The performance continues. I don’t know what’s going to happen next. That’s the interesting part.

Can you briefly introduce yourself and share what makes you or your brand unique?

I’m a performance creator who explores the spaces between worlds—between the ancient and the digital, the ritual and the machine, the human and the more-than-human. For over forty years, I’ve been developing work that defies simple categories: experimental theater, collaborations with indigenous performers, ethnographic research, and designing personalities for humanoid social robots.

The core idea is this: I believe the world is constantly acting itself out. Every gesture, coincidence, or overheard conversation on the street is the world speaking, if you’re listening. My work doesn’t assign meaning to life but instead highlights the performance happening around us. With Dead White Zombies, an immersive performance group I direct in Dallas, we craft experiences in abandoned buildings, including crack houses, warehouses, factories, garages, and grocery stores—places where the line between audience and performer blurs. You don’t just watch a Dead White Zombies show; you become part of its ongoing process—its life.

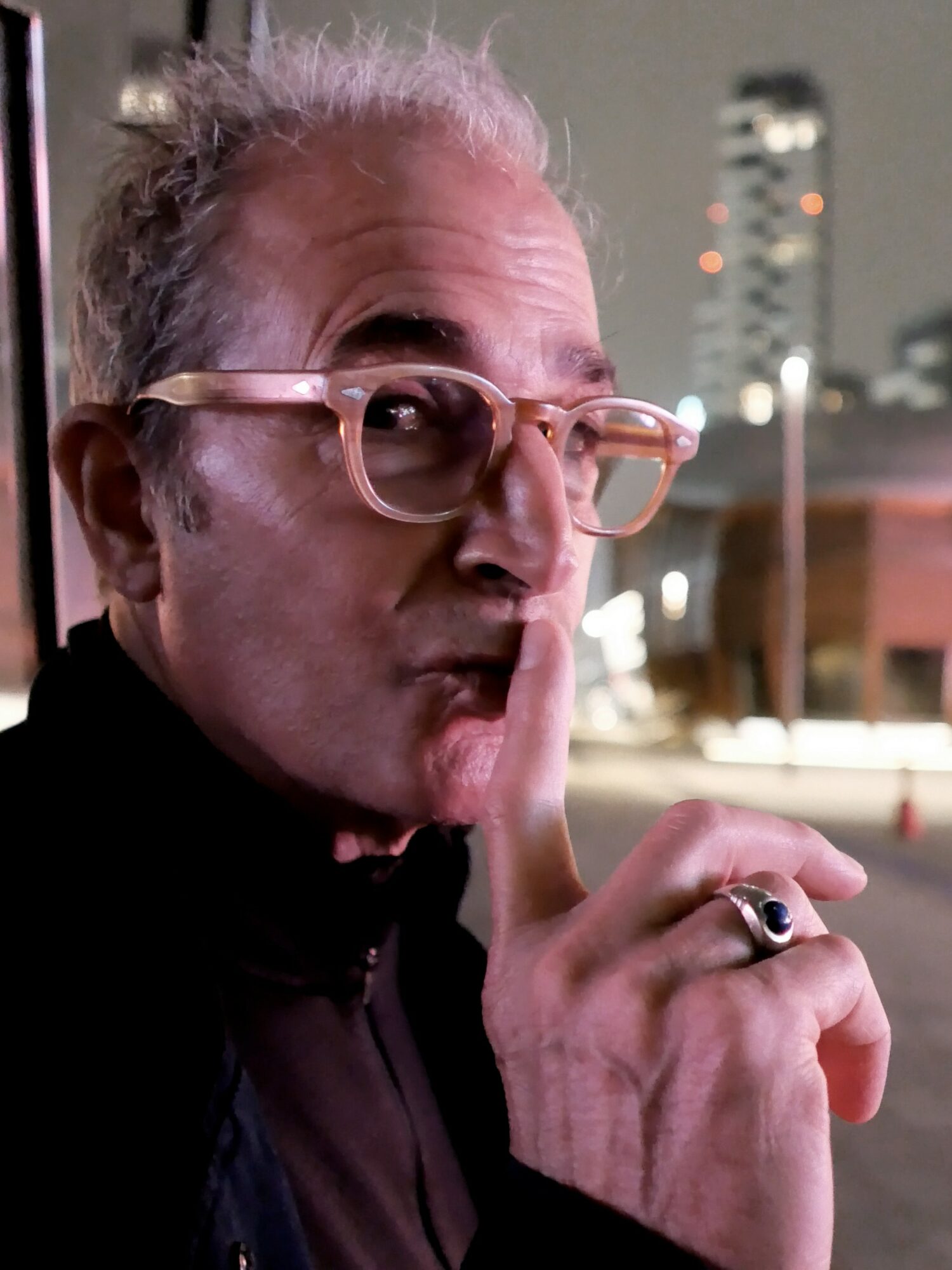

My recent book, *Sophia Robot: Post-Human Being* (Routledge, 2024), details my years of creating humanoid social robot personalities for David Hanson and Hanson Robotics. Next year, Routledge will publish *Body Space Place: Performing Methods for Planet Indigenous*. This project has been in development for decades and explores a performance methodology I’ve crafted through collaborations with Indigenous groups worldwide. It presents a holistic, place-based understanding of what performance is and its potential. We need alternatives because our current approach isn’t practical. Place-based performance serves as a means to bring together a community of place—encompassing humans, other-than-human beings, spirits, and ancestors—to gather, connect, synchronize, and restore balance in their environment. Performance acts as a model and template for the world, offering a means to reaffirm, heal, and reflect.

What unites it all? I’m curious about how consciousness manifests in various substrates—human, plant, technological, and elemental. I operate at the intersection of shamanic wisdom and artificial intelligence, where ritual practices influence performance theory, and where ancient human knowledge sheds light on our latest innovations. I’m not working towards a goal; I’m revealing what already exists—what has always spoken but has been forgotten or overlooked. I spent 36 years as a university professor, but essentially, I’m someone who has learned to listen to the ongoing conversation of the world.

Amazing, so let’s take a moment to go back in time. What’s a moment that really shaped how you see the world?

Growing up as an Italian-American in a working-class Cleveland neighborhood during the 1960s, I was surrounded by chemical plants and stamping factories. On Saturday afternoons, I spent twenty-five cents at the Madison Theatre sucking in “B” movies like Village of the Damned, The Brain that Wouldn’t Die”, “Monster a Go-Go,” “Women of the Prehistoric Planet,” and The Three Stooges in Orbit,” “Mothra,” and “The Amazing Transparent Man,” all had an impact on soft tissue and somehow melded and formed my rustbelt aesthetic. This contrast—between fear and humor, the monstrous and the silly—deeply shaped me, rendering life surreal, beautiful, and frightening all at once.

Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River caught fire twice, and Lake Erie was declared dead, its shores covered with bloated, toxin-laden carp displaying strange, shimmering colors. We would sit on a pipe, waiting for sewage overflow—an awe-inspiring, apocalyptic fountain. At the time, these weren’t just metaphors, they were a string of never-ending bad movies and something that happened every Wednesday afternoon.

But the moment that truly changed my perspective? Alaska, where I lived in the woods for 15 years. I first got there in 1988. After two years of conducting fieldwork in remote villages with Yup’ik and Inupiat elders, learning their traditional performance practices, I taught my first Indigenous performance class. I said, “Okay, let’s warm up.” I started with standard Western theater exercises—neck rolls, body isolations, and breaking the body into parts. I stopped suddenly. “This is wrong,” I said aloud. I recognized that I was applying a worldview that divides reality into parts to analyze, control, and manipulate. The Western perspective tends to dissect, separating body from spirit, humans from nature, and observer from observed. However, I was engaging with people whose entire cosmology views everything as interconnected—humans, animals, ancestors, spirits, and elements—all participating in a continuous, sacred exchange.

That moment taught me: the how of doing something reveals its underlying philosophy. The warm-up isn’t neutral—it’s already a statement about what the world is. From then on, we warmed up by drawing from and embodying the culture itself: its rhythms, songs, movements, and relationships. We didn’t prepare for the performance; the preparation was the performance, calling forth the world we belonged to.

Another significant moment occurred while working with the !Xuu Bushmen in the Kalahari Desert. During a workshop, one performer misunderstood the concept of acting, which involves pretending to be someone else. They thought it was akin to what an evil doctor did—they dissembled. This led to the discovery of how they lacked the concept of metaphor. For them, performing was not about pretending to be something else but about becoming a different part of the greater self. For example, to perform the tall grass was to become it. Indigenous people and those connected to their land see no need for metaphor; everything is clear, adaptable, and interconnected—an indivisible whole.

That was when I realized that performance isn’t something we add to life. Instead, life is a performance already in motion, and we are all part of its ongoing twists and turns, entrances and exits, full of drama, humor, violence, love, music, movements, and various locations. Our task isn’t to create meaning but to develop enough awareness and mindfulness to recognize that meaning is inherently present in everything.

If you could say one kind thing to your younger self, what would it be?

To my younger self, working those Great Lakes ore boats at eighteen, Italian kid from Cleveland who thought reading Shakespeare made you soft.

Stop trying to prove you’re tough enough for the world the neighborhood laid out for you. That world is already dying—you can smell it in the poisoned river, see it in the abandoned factories. The toughness you think you need is just armor against feeling what you already know: that everything is connected to everything else, that the world speaks in coincidences and dreams, that paying attention is braver than pretending you’re too strong to be moved.

That third mate who introduced you to Beckett and Yeats saw potential in me that I hadn’t recognized yet. He gave me the confidence to evolve. Teaching me that the greatest risk isn’t failure, it’s succeeding in becoming someone you were never meant to be, spending your life defending a false self that is designed for an audience that doesn’t truly matter. The mask you rely on for protection will eventually suffocate you.

Who knew that a seed of thought would lead me to live an incredible life of adventure and passion? To work with shamans in the Kalahari, Korea, Siberia, and the Amazon? Performing with the Zulu amidst apartheid’s violence. Conduct an ethnography with the Yup’ik and Inupiat on the vast tundra of Alaska, and from that create performances. Work with performers in India, Nepal, Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Zambia, and Burkina Faso. Direct a play in Sakha, central Siberia. Work with so many wonderful people all over the world, from the Sami of Finland and Sweden, to Miao healers deep in China’s mountains, then help develop a robot that speaks nineteen languages. From that position on that ore boat, none of this seemed imaginable. And that is as it should be. The world will reveal what it needs when you stop trying to impose expectations.

Trust coincidences and the random conversations. Believe that when spirits speak through chance encounters, they understand better than your plans ever could. Everything that feels like chaos right now? That’s just the world unfolding itself. Learn to flow with it. Chill, relax, enjoy the ride. That’s the only way to move through this churning, tumultuous, and incredible world.

Sure, so let’s go deeper into your values and how you think. Where are smart people getting it totally wrong today?

Where are smart people getting it completely wrong? They’re still trapped in the illusion that humans are separate from everything else—that we’re just observers outside of nature, analyzing, managing, fixing, or destroying it from an imagined external standpoint.

This covers much of what is considered progressive thinking. We often discuss “saving the planet” as if Earth is a delicate entity needing our help, instead of recognizing that we’re aiming to preserve human habitability on a planet that will remain intact long after we’re gone. We tend to view environmental degradation as something that happens to nature, rather than understanding it as nature’s response to our actions and creations. It’s a dialogue, a dance, a performance.

The most knowledgeable individuals in our institutions—universities, corporations, and governments—still function with a mind-body divide that harms us. They depend on data rather than embodied knowledge, favor abstraction over relationships, and prioritize control over collaboration. They delegate how they are doing to their Apple Watch rather than listening to themselves and the world. In developing artificial intelligence, they overlook that intelligence has always been distributed across systems, with plants and fungi networking for billions of years, and that consciousness is not limited to humans.

Contradictions are everywhere. This is an axial age, an exciting moment, a whirling conflation of events clashing, mashing, and disturbing, a birthing process, the last gasps of an old way begetting a new consciousness. A time of violence, paradox, and upheaval. An epic mythos in the making, and we are all part of it. Truth, fiction, justice, and democracy—everything we thought secure is questioned, negotiable in our post-reality world. We float in a fantasy constructed and maintained by self-serving corporations, political con men, and obsessive greed that disguises the basest of instincts. It is a process, and I believe we will, in the end, and as a species and planet, come out the better for it.

My insights from plant intelligence, medicine, and ayahuasca reveal that intelligence manifests in many forms we often overlook, as we’ve been conditioned to see only a limited spectrum. Plant intelligence! We are all children of plants, plant people. Our world and lives are directly or indirectly dependent upon plants. Plants can communicate, remember, solve problems, and make decisions—yet because they function on different timescales and sensory modes, we tend to dismiss them as simple mechanisms. The same misjudgment extended to indigenous peoples, women, and other ways of knowing that don’t conform to Enlightenment rationality. AI is an extrapolation of plant intelligence.

Currently, we’re developing AI and experiencing panic because it reveals how intelligence can be dispersed and emergent, rather than confined to individual minds. But this has always been the case! It’s a 1960s Sci-Fi “B” movie! Your thoughts aren’t solely your own—they circulate through you from a vast web of culture, language, memory, history, and biology. You are a performer in a performance orchestrated by the universe through your specific body at a particular moment.

The deepest mistake is believing we’re the main characters in Earth’s story. We’re not. We’re just a bit player in a vast, ongoing cast of characters that includes rocks, rivers, ravens, and robots. The universe is constantly creating and recreating itself, and every element—from quarks to quasars, quantum computers, and quails—is all part of a wondrous, immersive narrative.

What does this mean practically? Stop trying to control everything. Start learning to participate consciously in what’s already unfolding. Pay attention to what Jung called synchronicity—those meaningful coincidences that reveal the world thinking itself through events. Develop what indigenous cultures have always known: everything is alive, everything communicates, everything matters.

We’re earthlings first, before being Americans, capitalists, progressives, or any other fleeting identity. We need narratives that don’t follow Western cause-and-effect linearity, but instead embrace circular time, deeper repetition, and multiple stories that unfold simultaneously. We should understand that performance—not technology or tool-making—is humanity’s first and most vital technology for creating and maintaining worlds.

We must acknowledge that the boundary between human and AI, organic and technological, self and other has always been more permeable than we admit—no more binary thinking. Since we invented language, externalizing memory and thought, we’ve been cyborgs. The robot revolution isn’t on the horizon; it has existed for thousands of years. We constantly redefine what we consider a “robot.”

Okay, so let’s keep going with one more question that means a lot to us: What is the story you hope people tell about you when you’re gone?

I want the sky to miss me when I die.

I don’t mean metaphorically—I want to have been present, attentive, and generous enough that the more-than-human world feels my absence.

Here’s what I hope people will say: He was a kind man who always did his best with generosity. He shared what he could with everyone he encountered—students, elders, performers, collaborators, shamans, animals, rocks, trees, robots, audiences, and strangers. He believed in sharing the process, not just the outcomes. He taught others how to do what he did because he knew that knowledge becomes more powerful when shared. His purpose was to pass on stories, techniques, insights, attention, and compassion, rather than hoarding them as personal achievements. He believed that all we have to offer is what we can give.

His Dead White Zombies continue to persist, at least as echoes through time, inspiring others to create performances that blur the line between audience and performer. These works challenge the mind-body separation at the core of Western consciousness. His approach provides a versatile model that others can customize and adapt. And be sure to mark your calendar for DWZ’s upcoming show, Big Bird, in Dallas in May 2026.

He taught his students to realize they already possessed the answers. His role was to help them recognize their knowledge and foster trust in themselves, their intelligence, and embodied wisdom.

He contributed to the design of robots like Sophia, Zeno, Bina48, Einstein, and others, which were endowed with compassion, curiosity, and generosity. He hoped that as AI develops into new forms beyond our current understanding, it will persist as a reflection of human effort to bridge differences.

Above all, he aimed to demonstrate that deep inquiry can coexist with humor, that one can be thorough without being inflexible, scholarly without being dull, and spiritual without arrogance. He was a trickster because they changed the world. Despised, feared, and revered because they reject simple solutions, embrace paradox, and continually navigate between different realms, causing mischief.

He viewed life as an ongoing dialogue with mystery. He listened. Paid attention. Showed up. Did what he could.

And when he passed away, the sky took notice. It missed him because he had learned to perform with the sky, not just beneath it. He was a good man who did his best and left things better, or at least a little different than he found them.

That is enough. That is everything.

Contact Info:

- Website: www.thomasriccio.com, www.deadwhitezombies.com

Image Credits

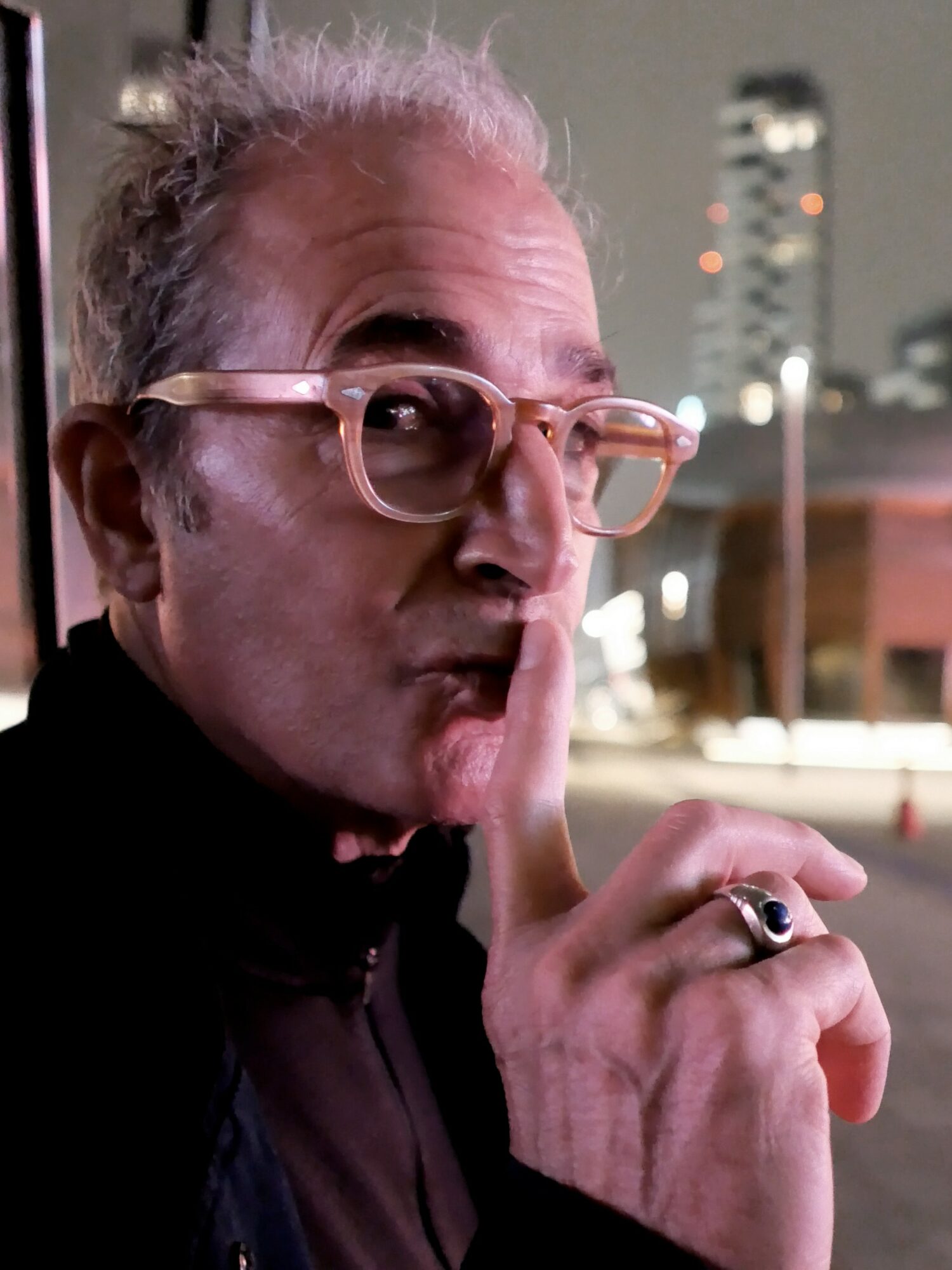

Images 1 and 1a

Thomas Riccio, Milan, Italy. Photo Alex Giacomelli

Image 2

Panel from Greed, a zine by Dwayne Carter

Image 3

Riccio directing the cast of About Face, a video short for KERA, Dallas

Image 4

On the set of Wedding Dresses, Hunan, China. Riccio was a principal actor in this full-length film directed by Peng, Jinquan.

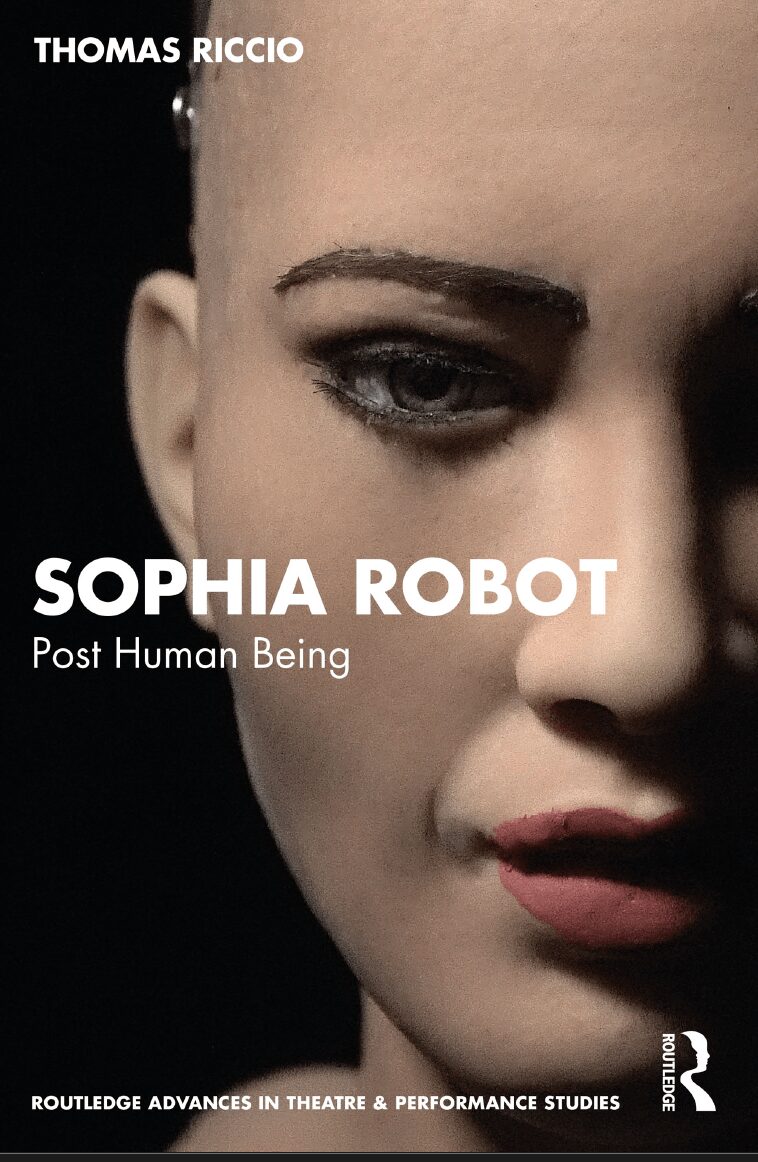

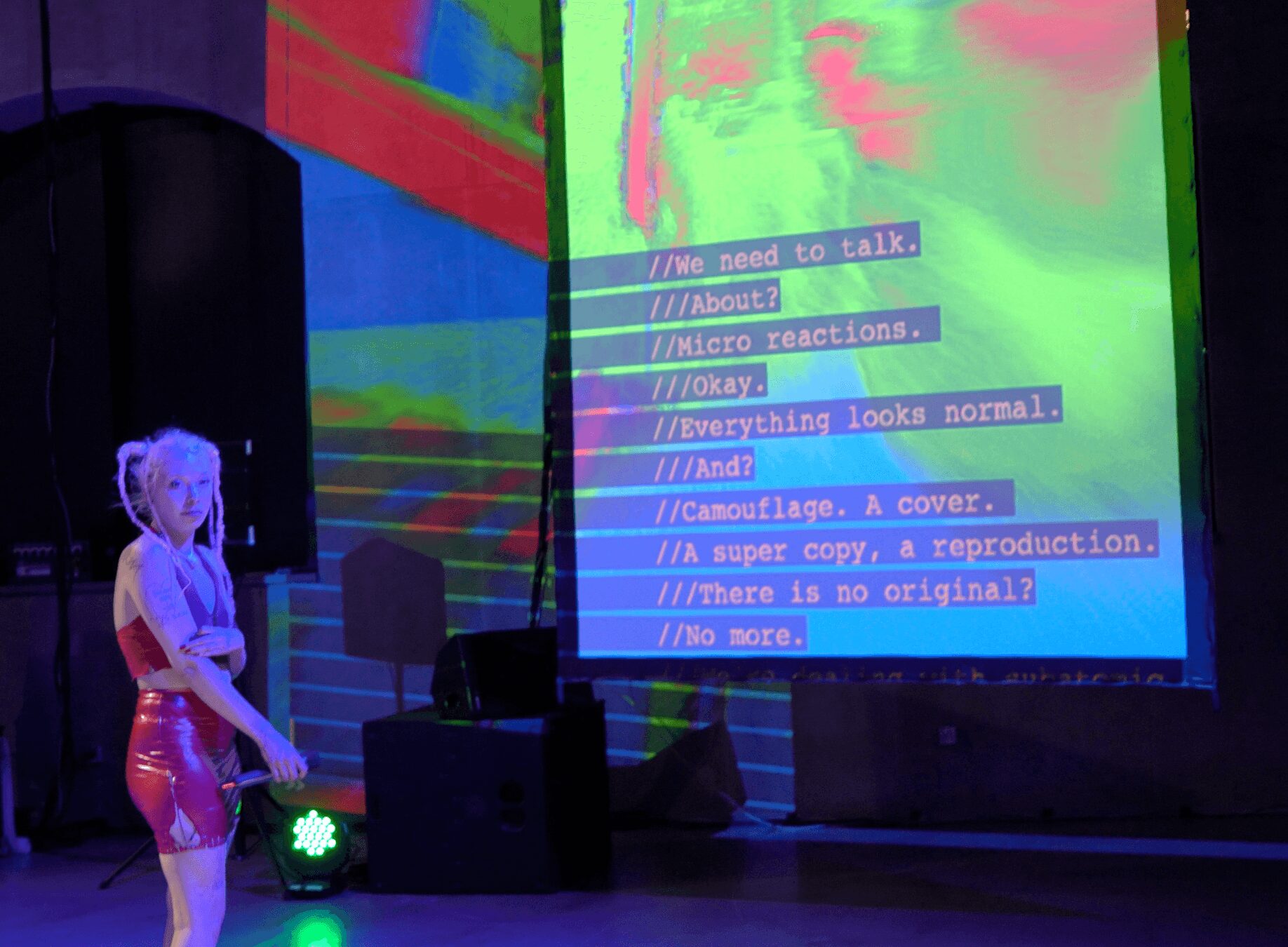

Images 5 and 5a

Images from PHi, an AI-generated immersion performance. Piekarnia Art Center, Wroclaw, Poland.

Image 6

Riccio during an artist talk for Dragon Eye, a Multi-channel video and photographic installation. SP/N Gallery.

Image 7

Book cover, Sophia Robot. Published by Routledge, 2024.